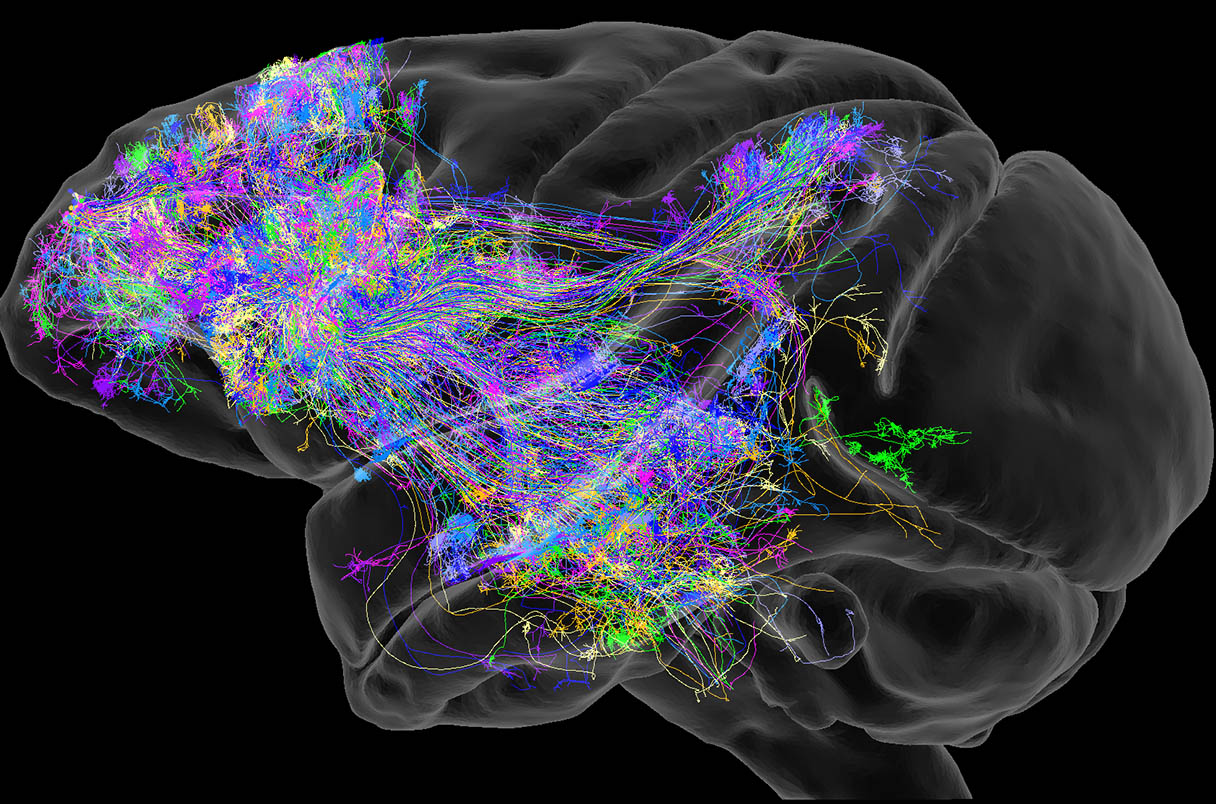

A recent map of 576 neurons in the prefrontal cortex of a macaque shows the cells’ projections to other brain areas. (Yanzhi Wang, Lingfeng Gou, AND Jun Yan/ Institute of Neuroscience, Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology/Chinese Academy of Sciences)

The human brain is by no means terra incognita. We’ve known for decades that memories form in the hippocampus and our fight-or-flight response stirs in the amygdala. But scientists are nowhere near a thorough inventory of our 86 billion neurons and roughly equivalent number of glial cells, much less a map of how different cell types join up into circuits to enable thought.

A new global collaboration intends to chart that terrain in exquisite detail. On 20 September, scientists from around the world gathered at a conference here to launch the International Consortium for Primate Brain Mapping (ICPBM). “We want to know the neural architecture underlying all the brain’s functions,” says ICPBM chair Mu-ming Poo, scientific director of the Institute of Neuroscience, Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The new consortium aims to analyze marmoset, macaque, and human brains to create so-called multiomic atlases, which would include all cell types; their patterns of gene expression based on RNA transcripts, or transcriptomes; and each cell’s projections across the brain. Set to run for 25 years, the effort will produce multiomic maps not just for monkeys but for developing, adult, aging, and diseased human brains from diverse populations

“The scale of what’s being proposed is mind-blowing,” says consortium member Marcello Rosa, a neuroscientist at Monash University. “You could dismiss some of the aims as unattainable even in 25 years,” he says, “except it was clear from the presentations that the technical issues are being worked out in a systematic manner.” Hongkui Zeng, director of the Allen Institute for Brain Science, who attended the conference but is not a consortium member, says the results “will have a tremendous impact on the field.”

ICPBM so far includes nine institutions from Australia, China, Germany, Hungary, India, South Korea, and Spain. Tensions with China have deterred U.S. institutions from signing on, although U.S. scientists are among the more than 100 individual participants from 25 countries. Shanghai authorities and China’s central government have pledged funding—the precise amounts are still under negotiation, Poo says—for the ICPBM, including a central hub that would establish facilities for imaging brain tissue at submicron scales, provide research materials such as human brains from autopsies, and maintain a web platform for data sharing. Other members will contribute their own samples, molecular studies, and mapping.

The potential payoff includes insights into cellular and molecular mechanisms behind neurological conditions from stroke to Alzheimer’s disease that could point to new treatments. The results might also hold clues to the cognitive processes that make us uniquely human.

The consortium will build on arduous efforts to map punier brains. Over the past decade, researchers have compiled complete atlases of the fruit fly and zebrafish brains at the level of individual cells and circuits. In December 2023, Zeng and dozens of colleagues unveiled an atlas of the mouse brain transcriptome, funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) BRAIN Initiative. She predicts that the mouse connectome—the complete wiring diagram of cells’ projections and synapses—is “achievable within 5 to 10 years.”

Yet a marmoset’s brain, half the size of a walnut, has twice as many cells as a mouse’s: more than 1 billion neurons and glial cells. A macaque’s brain, the size of an avocado, has about 13 billion total cells, and our grapefruit-size brains another order of magnitude more. “No single institute or nation can comprehensively map the primate brain at the required scale,” says ICPBM member Dong Won Kim, a neuroscientist at Aarhus University. “Pooling expertise, technologies, and data is probably the only realistic way to achieve this in a reasonable timescale.”

China is quickly developing technologies that could speed single-cell transcriptome analysis of larger brains and the mapping of their intricate connectomes, says Poo, an éminence grise of neuroscience who has helped shape the ongoing China Brain Project, one of the largest basic research initiatives the country has ever undertaken.

One promising technology is a single-cell sequencing platform called Stereo-cell, which the Shenzhen-based company BGI Group recently unveiled in Science. Its developers say it can capture the transcriptomes of up to nearly 1 million cells in a droplet loaded on a single chip, and it can also sequence degraded RNA from brain samples preserved in paraffin.

Even though understanding the human brain is the ultimate goal, there are good reasons not to stake the entire project on human samples. Access to human brains depends on people willing to donate their tissue postmortem, and the preserved material “will never be as good as the anatomy achieved from animal studies,” says ICPBM member Andrew Parker, a neuroscientist at Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg. For instance, the fine details of marmoset brains, despite their differences from humans, might help explain what makes primate intelligence different from other mammals, says another ICPBM member, neuroscientist David Kleinfeld of the University of California San Diego.

Poo says high-resolution, whole-brain imaging facilities in Suzhou, Hainan, and Shenzhen give China an edge in nonhuman primate brain mapping. Its scientists also face fewer regulatory barriers to invasive procedures in living monkeys, such as wiring up their brains or injecting them with dyes for imaging. Poo vows ICPBM will meet or exceed ethical standards in all member countries.

The project’s international collaborators bring other assets. For example, the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, is charting cell types in scores of human brains from autopsies, Iran is establishing a national primate facility in Tehran, and a coalition of Asian synchrotron facilities called SYNAPSE plans to use the intense x-rays generated by the accelerators to map a human brain at subcellular scale. “Fingers crossed that this consortium will survive” the isolationism many countries are embracing, says Aarhus neuroscientist and ICPBM member Chao Sun.

The U.S. is already largely excluded from the China-led initiative. NIH in recent months has thrown up new hurdles to cooperating with labs overseas—though a handful of foreign collaborations under the BRAIN Initiative are continuing. Zeng notes that U.S. and Chinese brain-mapping efforts are “highly complementary” given that the BRAIN Initiative has largely focused on molecular studies of mouse and primate brains and has only just begun pilot studies of anatomical mapping. Even though the Allen Institute is “not able to collaborate directly [with ICPBM] at this time,” Zeng says, “I hope coordination can continue.” (Science)

86-10-68597521 (day)

86-10-68597289 (night)

52 Sanlihe Rd., Xicheng District,

Beijing, China (100864)